The three-point memo Earth needs us to get. And now.

As humans across the globe raise their voices in recognition of Earth Day, we’re taking a beat to listen and reflect. Listening to a diversity of voices speaking up on behalf of our tiny blue planet can be a lovely and worthwhile thing for all of us to do—this day and every day.

But these voices can sometimes contradict each other. Even with a shared stake in creating a more livable world, these voices can get loud and divisive. They can distract. But there is a single voice that cuts through all of this, and it’s the one that has our ear the most these days.

It’s the Earth herself.

Listening to her takes many forms, including close observation of her climate patterns, her soil health, and the life in her lands and waters. She is the inspiration in pretty much all we do at GFI (including gracing the pages of our recently published 2020 Year in Review. Check it!)

That said, we imagine she is not so inspired by all of us humans these days. If she were the stern-memo-writing type, we’re fairly certain she would be clear and plain with her feedback. She would take us to task on multiple fronts. She would cite examples in excruciating detail, bring receipts, and furrough her brow. But like any good boss (and have no doubt, she is the boss), she’d also provide guidance. She would lay out her most basic rules of life in the clearest of terms. She would literally show us the way.

On this Earth Day 2021, we’re taking honest stock of how GFI’s actions heed three of her most foundational rules, each of them core concepts in Earth science and ecology. We invite everyone out there to do the same.

1. Competition and collaboration are not mutually exclusive.

Among the most fundamental concepts and questions in ecology is how different species can coexist in nature. There is clear evidence of competitive interactions among and within species, as they strive to survive. Yet in these same communities, cooperative loops and shared networks exist. From the tiniest bacteria to the most giant of trees, examples from nature show us how a mix of competition and cooperation can produce benefits beyond the individual, helping the entire community.

Consider what this past year revealed about how competition can coexist with collaboration. When countries all over the world shut down and locked borders to battle a novel coronavirus, what did scientists do? Many put aside their individual research pursuits and institutional agendas to collaborate on a scale unlike any in history, developing vaccines for the entire world in record time.

If success for all is the goal, then it’s not only possible to collaborate with those you may normally view as competitors, it’s imperative.

This core concept is central to GFI’s theory of change, which is focused on shifting systems. Like natural ecosystems, the systems that we focus on are complex and ever evolving. Like natural systems, there is competition for resources, territorial disputes, drama, and conflict of all sorts. There are also networks of support, collaborative strategies, and an instinctual sharing of resources.

In nature, ecosystem health depends on these complex dynamics and co-dependencies. The food system we aim to change is no different.

To be clear, we are working with a diversity of people and partners to transform the food system in fundamental, default-shifting ways. Fully aware of the enormity of this system, we focus on advancing science, policy, and markets to help the world produce protein with far fewer resources and climate-altering impacts. Across these sectors, we’re working to advance alternative proteins—mostly plant-based and cultivated (cell-based) meat.

We acknowledge that in some respects our competitors are those vested in the current animal-based food system. But if our goal is a sustainable, secure, and just food future for all, collaborating with competitors with a shared eye on the global good is not only possible, it’s essential.

Project Drawdown’s Dr. Jonathan Foley recently touched on this when he likened the climate crisis to a game of chess. “We need to use all the pieces, employ multiple strategies, and see the whole board. But unlike chess, we have to play this game collaboratively to win.”

“We need to use all the pieces, employ multiple strategies, and see the whole board. But unlike chess, we have to play this game collaboratively to win.”

Dr. Jonathan Foley, Executive Director of Project Drawdown

Consider the brain trust across all stakeholders in this space: Farmers and ranchers with intimate knowledge of local lands and waters. Scientists with intimate understanding of biological systems and processes. Industry innovators with expertise in sustainable supply chains. Policymakers working to protect the public commons. What if we could channel all that knowledge and intensity in the same damn direction: toward feeding the world in ways that enable a greater diversity of life to survive and thrive. What would that look like, to be both competitors and collaborators?

On this front, we have more work to do. But we are widening our own path, making room for both competitors and collaborators along the way. Just last month, we, along with 60 nonprofits, trade associations, and companies, submitted a letter to Congress requesting support for federal investment in alternative protein research. Among the signatories were a host of nonprofits, research institutions, consumer groups, and companies of all sizes, including large multinational companies such as Unilever, Merck KGaA, and Kraft Heinz. Trade group signatories included the American Mushroom Institute, USA Dry Pea & Lentil Council, and Plant Based Foods Association. NGO signatories included Greenpeace, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Consumer Reports. Each entity who signed is playing collaboratively, knowing that’s exactly what it will take to transition to a better food future.

Widening the path is also central to this year’s U.N. Food Systems Summit, for which GFI has been tapped to serve as the Innovation Lead for one of the Summit’s five action tracks. Leading up to the summit in October, key players in science, business, policy, healthcare, and academia, as well as farmers, indigenous people, youth organizations, consumer groups, and other key stakeholders will contribute bold new strategies aimed at achieving progress on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

Governments, too, are beginning to step up. Just last week, U.S. Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro made remarks at the Department of Agriculture’s Year-Ahead Hearing that called for “parity in research funding for alternative proteins,” going on to say: “The United States can continue to be a global leader on alternative protein science, and these technologies can play an important role in combating climate change and adding resiliency to our food system.”

“The United States can continue to be a global leader on alternative protein science, and these technologies can play an important role in combating climate change and adding resiliency to our food system.”

U.S. Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro

What would it look like for governments around the world to be both competitors and collaborators in transforming the global food system? It’s this exact scale of global focus and collaboration that can revolutionize how we make meat, eggs, and dairy, transforming agriculture into the climate-forward food system that the world needs it to be.

2. Transitions happen. Adapt.

Another core Earth science concept is ecological succession—a process of change in the species structure of a community over time. An ecological community may begin with relatively few pioneering plants and animals. But as it develops and adapts, it becomes more diverse and complex, increasing its stability until it becomes self-perpetuating. Imagine grassy fields, followed by brush, then small trees, and finally forest.

While an oversimplification of a complex concept (asking for grace here from any ecologists still reading), the key messages are clear: Adapt. Diversify. Be self-sustaining.

Our current food system is not taking any of these cues. Not one.

To meet global climate goals, we must fundamentally transform our food system. Earlier this month, GFI and Climate Advisers co-published “A Global Protein Transition is Necessary to Keep Warming Below 1.5°C,” a policy report outlining why such a transition is required if the targets laid out by the Paris Climate Agreement are to be met. Simply put, the world will not get to net-zero emissions without addressing food and land. Alternative proteins are a key aspect of how we do that.

An agricultural transition toward alternative proteins could significantly reduce emissions, starting now with shifts in crop production. By growing more food crops for alt protein products as compared to feed crops for livestock, we can eliminate massive inefficiencies and harmful externalities from the supply chain. Primary crop ingredients can be converted directly into end products rather than inefficiently converted to protein through animal metabolism. (Check out GFI’s research grant projects, many of which focus on identifying and assessing plants most suitable to serve as the next wave of alternative protein crops.)

Transitioning to a socially just, net-zero emissions world will require governments to invest big-time in research, development, demonstration, and deployment of every decarbonization tool available. Alt proteins can be a decidedly powerful tool, with the potential to create high-quality jobs and careers, prevent pollution, and lessen our reliance on finite land and water resources for food production.

Alt proteins can be a decidedly powerful tool, with the potential to create high-quality jobs and careers, prevent pollution, and lessen our reliance on finite land and water resources for food production.

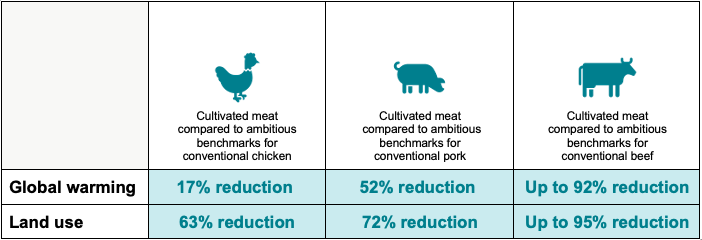

Just last month, GFI shared results from a life cycle assessment and techno-economic assessment conducted by independent research firm CE Delft, which modeled a cultivated meat facility operating in 2030. Informed by data contributed by companies involved in the cultivated meat supply chain, the analyses show that—compared with conventional beef—meat cultivated directly from cells can result in up to 92 percent less global warming and 93 percent less air pollution and use up to 95 percent less land and 78 percent less water when renewable energy is used in production of both.

While cultivated meat isn’t yet widely available (unless you’re in Singapore), plant-based meat available today carry a much lighter environmental footprint than conventional animal-based products, resulting in significantly less greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and aquatic nutrient pollution.

More broadly, a shift to alternative proteins goes hand in hand with policies and practices that incentivize the restoration of agricultural land for its ecosystem services potential. Alongside renewable energy, carbon markets, and conservation incentive programs, alternative proteins can move us from an extractive economy to a restorative economy. With access to new income streams, farmers, ranchers, and other stakeholders with intimate understanding of local lands and waters can enjoy livelihoods funded by ecological restoration, carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery, and rewilding.

Transitions happen. We need to be clear on which transition we want, then work together to get there.

Transitions happen. We need to be clear on which transition we want, then work together to get there.

3. Diversity strengthens resilience.

This third rule plays out in pretty much every realm on earth: The more biodiverse an ecosystem is, the more resilient it is.

Ecosystems are incredibly complex hubs of life. While the science of ecosystem resilience continues to evolve, specific factors are known to play a role: the diversity of life forms in that system, interactions between those life forms, and the environmental conditions in which they interact.

We hear the boss-lady loud and clear on this one. We have experienced first-hand how bringing a diversity of people together—representing multiple sectors, perspectives, disciplines, and lived experiences—strengthens the field.

- Our Alt Protein Project is a global student movement dedicated to turning universities into engines for alternative protein education, research, and innovation. From driving scientific inquiry to creating educational programs and establishing a talent pipeline for a growing industry, universities will be a cornerstone of the alternative protein ecosystem.

- Our GFIdeas Community, currently comprising more than 1,300 entrepreneurs, scientists, students, and subject matter experts, drives alt protein innovation across the global food ecosystem. Every single member of the GFIdeas Community is an individual force of nature, each made stronger, smarter, and better by the diversity of those around them. Access to GFIdeas is 100 percent free to all participants regardless of means, a supportive “environmental condition” made possible by GFI’s generous donors.

- GFI’s international network of affiliates also reflects the strength of diversity. As a global think tank and open-access resource hub 100 percent powered by philanthropy, GFI is able to advance alt protein science and research, mobilize resources and talent, and empower partners across the food system to create a sustainable, secure, and just protein supply. The diversity of this global team is the source of its impact and influence.

So while we’ve made some progress on Earth’s three-point memo, we clearly have hard work ahead. We need to be widening the path. We need to be easing the transition. And we need to be growing and supporting a diverse and global talent pipeline who can tackle one of the biggest challenges of our time.

As a relatively young nonprofit focused on tilting the world toward a better food future, we know success is not inevitable. If our recently released 2020 Year in Review is any indication, however, each year gets us closer to a world where alternative proteins are no longer alternative. Thanks to the generous support of donors and other supporters who see themselves in this global goal, we can get there together.

Happy Earth Day, humans.