The nutritional profile of plant-based meat

Dive into our in-depth overview of the nutritional profile of plant-based meat, highlighting both its strengths and opportunities for improvement compared to conventional meat. This comprehensive resource offers valuable insights to support product development, reformulation, consumer messaging, and research initiatives.

Read our full white paper

The nutritional profile of plant-based meat: overarching considerations

When considering the nutritional quality of plant-based meat products, it is important to compare them to conventional meat products. Plant-based meat is intended to be eaten as a substitute for conventional meat, rather than replacing other plant-based protein foods, such as beans or lentils.

With respect to nutrient content, there is considerable variation in the nutritional composition of plant-based meat products, as is the case with conventional meat products. This variation exists both across product categories (e.g., burgers, chicken, sausages) and across brands and products within a single category.

Also, while plant-based meats are generally ultraprocessed, unlike other ultraprocessed foods they are healthier than the foods they are intended to replace and generally don’t have other negative characteristics typical of ultraprocessed products.1

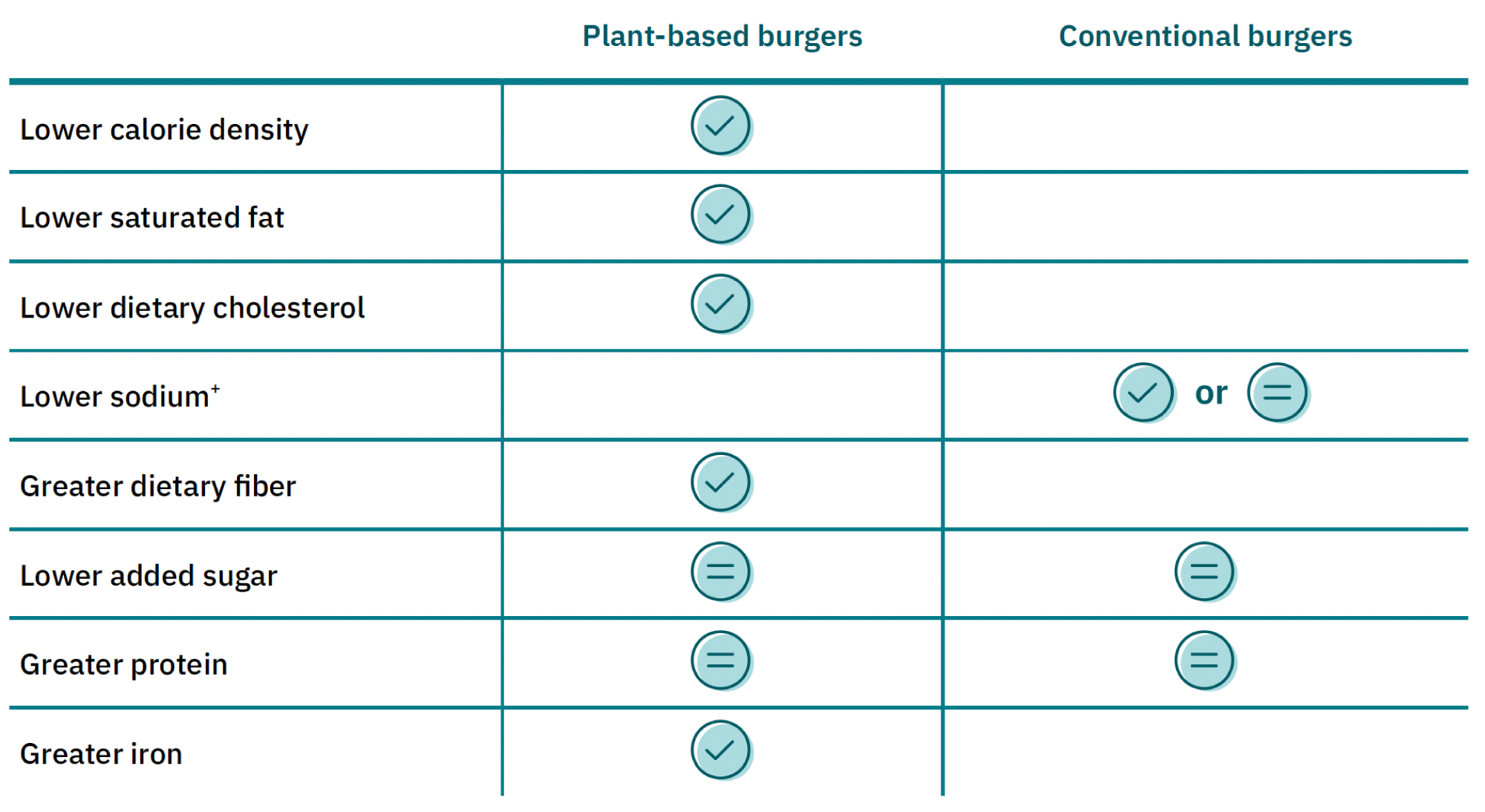

Table 1: Nutritional comparison of plant-based and conventional burgers*2

+ Sodium is often added to conventional burgers during preparation and cooking. Research comparing diets high in plant-based meat with diets high in conventional meat finds no significant difference in total sodium intake.3

Nutritional strengths of plant-based meat

The nutritional profile of plant-based meat has several advantages over conventional meat. Plant-based meat is lower in calories and saturated fat, free from cholesterol, a good source of fiber, and associated with positive health outcomes.

Cardiovascular effects

A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing the cardiovascular effects of intake of plant-based or fermentation-derived meat with conventional meat found that replacing conventional meat with plant-based or fermentation-derived meat lowered total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease,4 the leading cause of death in the United States.5

In addition, a 2024 literature review found that plant-based meats generally align with recommendations for improving cardiovascular health due to their low saturated fat, high polyunsaturated fat, and dietary fiber.6 To reach this determination, the review referenced several studies in which participants replaced conventional meat in their diets with plant-based alternatives, resulting in improvements to total and LDL cholesterol and reductions in body weight.6

Lower calorie density

U.S. and international studies have found that plant-based meat is lower in calories than conventional meat both on a per serving basis and when product weight is standardized.2, 7 Consuming foods high in calorie density (also called energy density), which refers to the calories per weight of food, can lead to weight gain, while research shows that consuming foods lower in energy density produces weight loss.8 Both U.S. and international trials have found that substituting plant-based meat in place of conventional meat can lead to weight loss.3, 4 About one in five American children and two in five adults have obesity,9, 10 increasing the risk for a range of costly chronic health conditions.11

Higher dietary fiber

Conventional meat contains little or no dietary fiber. Both U.S. and international analyses have found that plant-based meat contains significantly more dietary fiber than conventional meat.2, 7, 12 While nutrient composition of plant-based meat products varies, some are a “good source” of dietary fiber, meaning they contain between 10 and 19% of an individual’s daily fiber needs, per serving.13 High intake of dietary fiber is associated with a lower risk of developing coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.14 Dietary fiber also has positive effects on the gut microbiome.15 Despite these benefits, most people eat less than half of the recommended amount (minimum of 28 grams per day of fiber for a 2,000 calorie diet).14, 16 More than 90% of women and 97% of men do not consume enough dietary fiber.16

Iron and other essential nutrients

Plant-based meat contains similar or greater amounts of iron compared to analog conventional products. A 2024 international systematic review found that, overall, plant-based meat contains more iron than conventional meat.12 A U.S. study found similar findings when product weight is standardized.2 More than 95% of plant-based meat products on the U.S. market contain iron.17

While international markets vary, a 2023 analysis of the nutrient content of varying types of plant-based and fermentation-derived burgers in the United Kingdom found that the amount of bioavailable iron in most products tested was comparable to beef burgers.18 Compared with beef burgers, the plant-based burgers had higher amounts of the essential minerals calcium, copper, magnesium, and manganese, which naturally exist in the plant proteins from which they are made. While the plant-based burgers were lower in zinc18 the bioavailable zinc was comparable in the fermentation-derived meat burger and the beef burger.18 International studies have shown that mycoprotein-based (fermentation-derived) plant-based meat products are rich in zinc.19 An international systematic review has found that, overall, plant-based meat is lower in zinc, but higher in calcium, than conventional meat.12 However, there is significant variation in micronutrient content among plant-based products, presenting opportunities for innovation.

Opportunities to improve the nutritional profile of plant-based meat

While plant-based meat has several relative nutritional advantages to conventional meat, opportunities exist to further improve its nutritional profile.

Sodium

Processed conventional meats are a leading source of sodium in U.S. diets.16 While raw whole cuts of conventional meat are low in sodium, salt is often added during preparation and cooking. The sodium content of plant-based meat products varies widely, and some plant-based meats contain moderate or high sodium levels.2 While reducing sodium as much as possible should be a long-term goal, even shifting high-sodium products to a more moderate level is a worthwhile interim step and would improve their nutritional quality.

While opportunities remain for reduction in sodium content in plant-based meat, evidence suggests that its present levels do not negate the observed cardiovascular benefits.6

Methylcellulose

Methylcellulose is a food additive that serves as a common binder, emulsifier, and thickener in many commonly eaten foods, including plant-based meat. It is considered safe by the FDA and the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) at levels typically consumed, based on multiple safety assessments.20, 21 However, some consumers have expressed concerns about such food additives.22 Additional research could help to identify potential alternatives for the unique texture and gelation properties of methylcellulose.

Fat quality

Plant-based meats vary in the type and amount of fat they contain. While both U.S. and international studies have shown that, overall, conventional burgers have more total fat and saturated fat2, 7, 12 than plant-based burgers, some plant-based meats may still be high in saturated fat.

Food processing

Plant-based meats typically meet the definition of ultraprocessed foods under the NOVA Food Classification System. However, they are generally healthier than the conventional meats they aim to replace and differ significantly in nutritional profile from many other ultra-processed foods.1 Ultraprocessed foods are defined as “industrial formulations typically with 5 or more and usually many ingredients. … Ingredients include food substances not commonly used in culinary preparations, such as hydrolyzed protein, modified starches, and hydrogenated or interesterified oils, and additives whose purpose is to imitate sensorial qualities of unprocessed or minimally processed foods and their culinary preparations or to disguise undesirable qualities of the final product. … ”23 The NOVA food classification system was originally intended as a sociopolitical designation and does not consider a food’s nutrient profile.24

Moreover, processing can enhance the nutrition of plant proteins. For example, extrusion processing improves the digestibility of sunflower protein and reduces the concentration of antinutrients.25 It has also been shown to minimize losses in vitamins and prevent foodborne illness.26, 27

Plant-based meats: an ultraprocessed exception?

Ultraprocessed foods are diverse, and studies that have considered the health implications of various subcategories of ultraprocessed foods have found that the health effects vary by subcategory. Adverse health outcomes tied to high consumption of ultraprocessed foods appear to be driven largely by sweetened beverages and processed meats.1 For example, studies published in the Lancet found that, unlike other foods classified as ultraprocessed foods, plant-based meat and milk intake was not associated with increased risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases28 or type 2 diabetes,29 while the opposite was true of processed conventional meat.28, 29 Other studies have found that processed meat (which plant-based meat is designed to replace), sugary drinks, and artificially-sweetened drinks were responsible for driving the majority of the increased cardiovascular risk30 and increase in total mortality31 associated with the ultraprocessed food group as a whole.

In support of these findings, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics stated in a 2025 position paper, “Although plant-based alternatives, including plant milks, meet the definition of ultraprocessed foods, plant-based alternatives have not been associated with the same negative health effects as other ultraprocessed foods such as sodas and ultraprocessed animal products. In addition, plant-based milks and other vegan foods intended to replace or serve as alternatives to animal-based foods may be key sources of nutrients.”32 Overall, the evidence suggests that plant-based meats may be a “rare ultraprocessed exception,” given the distinct nutritional profile compared to typical ultraprocessed foods and generally favorable health profile relative to the conventional meat products it is intended to replace.1

Potential actions and next steps

Food industry leaders, policymakers, researchers, public health and health care professionals, and other stakeholders can take action to improve the nutritional profile and overall healthfulness of plant-based meat as a category.

Improving the healthfulness of plant-based meat and educating consumers can motivate them to choose plant-based over conventional meat. However, these benefits only matter if the products also deliver on core consumer needs around taste and price. These expectations must be met for consumers to consider plant-based meat, and there is still work to be done on that front.

More research is needed

Many potential improvements to the nutritional profile of plant-based meat require additional research. Both academic research and industry research and development (R&D) are needed.

With respect to independent academic research, longer duration studies on the health effects of plant-based meat intake could help clarify the long-term benefits of regular intake of plant-based meat. Most trials on the health effects of plant-based meat that have been conducted to date are relatively short (e.g., 4-12 weeks),33 while it can take many months, if not years, to see changes in some disease indicators or risk factors. In addition, most studies to date have been conducted using relatively small sample sizes (e.g., 20-50 participants).33 Studies using larger and more diverse sample sizes and a range of plant-based meat products of multiple types and brands could help to further the evidence base on the health effects.

Consumer education

As many consumers lack familiarity with plant-based meat and an understanding of its ingredients, opportunities exist to better educate consumers about the health benefits of plant-based meat. In particular, there is a need to improve consumer understanding of the steps involved in plant-based meat production and ingredient processing. There is also an opportunity for increased education about the interplay between ultraprocessed foods and plant-based meats, as well as the nutrition and health benefits of plant-based meat compared with conventional meat.

Public policy

Changes to public policy could help increase intake of plant-based meat and improve its healthfulness. Some public policy opportunities could include:

- Increased investment in public sector research programs focused on overcoming barriers to improving the nutritional quality of plant-based meat and increasing understanding of the health implications of its intake.

- Improved integration of plant-based meat into updates to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and associated materials, such as MyPlate.

- Ensuring that any U.S. government nutrition targets consider plant-based meat as a category separate from other ultraprocessed foods, such as candy, chips, and cookies, given their different nutritional profiles.

Increased collaboration

Many of the challenges and opportunities to improve the nutritional profile of plant-based meat are consistent across the category. Thus, improved collaboration on topics including research, consumer education, and public policy engagement has the potential to benefit companies across the sector.

References

1. Greger, M. Are ultra-processed plant-based meats better than the alternative? Clinical Nutrition Open Science 61, 241 (2025).

2. Cole, E., Goeler-Slough, N., Cox, A. & Nolden, A. Examination of the nutritional composition of alternative beef burgers available in the United States. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 73, 425–432 (2022).

3. Crimarco, A. et al. A randomized crossover trial on the effect of plant-based compared with animal-based meat on trimethylamine-N-oxide and cardiovascular disease risk factors in generally healthy adults: Study With Appetizing Plantfood-Meat Eating Alternative Trial (SWAP-MEAT). Am J Clin Nutr 112, 1188–1199 (2020).

4. Fernández-Rodríguez, R. et al. Plant-based meat alternatives and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 121, 274–283 (2025).

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Leading Causes of Death. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm.

6. Nagra, M., Tsam, F., Ward, S. & Ur, E. Animal vs Plant-Based Meat: A Hearty Debate. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 40, 1198–1209 (2024).

7. Nájera Espinosa, S. et al. Mapping the evidence of novel plant-based foods: a systematic review of nutritional, health, and environmental impacts in high-income countries. Nutrition Reviews 83 (2025).

8. Stelmach-Mardas, M. et al. Link between Food Energy Density and Body Weight Changes in Obese Adults. Nutrients 8, 229 (2016).

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. (2025). https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult-obesity-facts/index.html.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Obesity Facts. (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html.

11. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Health Risks of Overweight & Obesity. (2023). https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/health-risks.

12. Lindberg, L., Mccann, R. R., Smyth, B., Woodside, J. V. & Nugent, A. P. The environmental impact, ingredient composition, nutritional and health impact of meat alternatives: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 149 (2024).

13. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. 21 CFR Part 101 Subpart D. Specific Requirements for Nutrient Content Claims. Code of Federal Regulations (1993). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-101/subpart-D.

14. Anderson, J. W. et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev 67, 188–205 (2009).

15. Fu, J., Zheng, Y., Gao, Y. & Xu, W. Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms 10, 2507 (2022).

16. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf.

17. Gallani, V. & Klapp, A. Building Bridges Between Habit and Health: An investigation into the nutritional value of plant-based meat and milk alternatives. ProVeg International (2024). https://proveg.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/INT_Research_Plant-based-alternatives-comparison_2024-1.pdf.

18. Latunde-Dada, G. O. et al. Content and Availability of Minerals in Plant-Based Burgers Compared with a Meat Burger. Nutrients 15, 2732 (2023).

19. Mayer Labba, I., Steinhausen, H., Almius, L., Bach Knudsen, K. E. & Sandberg, A. Nutritional Composition and Estimated Iron and Zinc Bioavailability of Meat Substitutes Available on the Swedish Market. Nutrients 14, 3903 (2022).

20. International Programme on Chemical Safety. 687. Modified celluloses (WHO Food Additives Series 26). INCHEM. https://www.inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v26je08.htm.

21. Methylcellulose (2025). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/section-182.1480.

22. Szenderák, J., Fróna, D. & Rákos, M. Consumer Acceptance of Plant-Based Meat Substitutes: A Narrative Review. Foods 11, 1274 (2022).

23. Gibney, M. J. Ultra-Processed Foods: Definitions and Policy Issues. Curr Dev Nutr 3, nzy077 (2018).

24. Chapman, J. Processing the Discourse Over Plant-Based Meat: Understanding nuance in the “ultra-processed food” debate to build acceptance and trust of plant-based meat. The Churchill Fellowship (2024). https://media.churchillfellowship.org/documents/JChapman_-_Processing_the_discourse.pdf.

25. Öztürk, Z., Lille, M., Rosa-Sibakov, N. & Sozer, N. Impact of heat treatment and high moisture extrusion on the in vitro protein digestibility of sunflower and pea protein ingredients. LWT 214, 117133 (2024).

26. Siitonen, A. et al. B Vitamins in Legume Ingredients and Their Retention in High Moisture Extrusion. Foods 13, 637 (2024).

27. Beniwal, S. Extrusion Technology and Its Effects on Nutritional Values. Food and Nutrition Science – An International Journal 07 (2023).

28. Cordova, R. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: a multinational cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe 35 (2023).

29. Dicken, S. J. et al. Food consumption by degree of food processing and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort analysis of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). The Lancet Regional Health – Europe 46 (2024).

30. Mendoza, K. et al. Ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular disease: analysis of three large US prospective cohorts and a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas 37 (2024).

31. Fang, Z. et al. Association of ultra-processed food consumption with all cause and cause specific mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ 385, e078476 (2024).

32. Raj, S. et al. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns for Adults: A Position Paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 0 (2025).33. Gibbs, J. & Leung, G. The Effect of Plant-Based and Mycoprotein-Based Meat Substitute Consumption on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Intervention Trials. Dietetics 2, 104–122 (2023).

33. Gibbs, J. & Leung, G. The Effect of Plant-Based and Mycoprotein-Based Meat Substitute Consumption on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Intervention Trials. Dietetics 2, 104–122 (2023).

Related resources

Americans understand plant-based meat labeling

Research shows that a large majority of American adults understand what plant-based meat products are based on current labeling.

How alternative proteins expand opportunities for farmers and agriculture

Explore our fact sheet to learn how alternative proteins support farmers, expand opportunities for agricultural livelihoods, and help create a healthy, resilient agriculture sector.

Alternative proteins are a global food security solution

Alternative proteins reduce supply chain risks, diversify the protein supply, and increase efficiencies of global food production.

The State of Global Policy: Alternative proteins

Our annual State of Global Policy report tracks public investment in alternative proteins and showcases the actions governments take to position themselves as leaders in the field.